John Gorlow

| Feb 22, 2019

This month I want to remove the clutter of misassumptions, doubts, and second-guessing about investment returns. I’ll provide an analytical framework for evaluating investment performance in any given year, regardless of market direction. I’ll demonstrate the life-changing value of remaining fully committed to a proven strategy, sticking with trusted fund partners, and choosing a fiduciary advisor like Cardiff Park. My aim is to dial down the financial noise, refocus your attention on vital facts, and free up mind-space for thinking and behaving strategically in order to make more informed investment decisions. First, a look at January markets.

Market Report

January 2019 Market Review

What a difference a month makes. US equities, as measured by the S&P 500, returned negative -14% in December 2018, the worst performance since 1931. Then came January, when the index roared back to gain 8.01%. It was the best January since 1987, which posted a 13.43% gain. With an impressive 15.01% climb from its December 24th low, strong upward momentum carried returns back into positive territory (0.26%) for the trailing three months. January’s gains erased the losses of 2018, but were unable to restore one-year returns (negative -2.31%) to positive territory. Trailing two-year annualized returns on the index improved to 11.12%, compared to 7.93% at the end of December.

A December-January turnaround was also evident in small caps. After returning negative -12.07% in December, the S&P SmallCap 600 roared back with a 10.64% return. But despite January’s U-turn, trailing three- and twelve-month returns remained in the red, -1.67% and -1.25%, respectively. With a longer yardstick, performance improved: the two-year annualized return for the Small Cap benchmark was 11.12%.

International developed markets, as measured by the MSCI World-ex USA Index, also rebounded, returning 7.41% for the month. The bounce resulted in a trailing 1.52% three-month return, versus negative -12.78% for the previous period. Despite this improvement, one-year returns were deep in the red at negative -12.06%. The two-year yardstick demonstrated continuing US outperformance, with global developed markets returning an annualized 8.60% compared to 5.36% ex-US.

Emerging markets rallied, as measured by the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, posting 8.1% for the period and 10.25% for the trailing three months. While the one-year return for the index remained in the red at negative -14.23%, the two-year return improved to an annualized 9.98%.

Both Domestic and International Real Estate securities outperformed. The Dow Jones US Select REIT Index returned 11.41%, while the S&P Global Ex-US REIT Index returned 9.69%. The results brought three-month returns to 6.77% and 9.48%, respectively. For the one-year period, foreign REITs remained slightly in the red at negative -1.50%, while US REITS posted a healthy 11.11%.

The 10-year US Treasury Bond closed the month at 2.64%, down from last month's 2.69%. Oil increased in price, closing at $54.13 from last month's $45.81. US gasoline prices decreased slightly, closing the month at $2.34 compared to December’s close of $2.35 per gallon. Gold was up, closing at $1,324.80 from last month's $1,284.70. For the month, the Bloomberg Commodity Total Return Index rallied along with equities, returning 5.45%.

From the macro perspective, the IMF reduced its 2019 global growth rate from 3.7% (October) to 3.5% (January). It also lowered its 2019 outlook for Europe from 1.9% to 1.6%. Growth rates for China and the U.S. were unchanged at 6.2% and 2.5%, respectively.

The US Federal Open Market Committee met and kept interest rates unchanged, also indicating that future interest rate increases were on hold. The Committee lowered its view of the US economy from “strong” to “solid.”

Feature Article

Thinking Long-Term

Have you ever believed you were on a brilliant course, only to discover the error of your thinking somewhere down the line? The multibillion-dollar financial industry thrives on this perpetual ping-pong game of optimism and regret, feeding on misassumptions, sloppy analysis and disregard of facts. The problem is that many investors never learn from their financial mistakes and are willing to adopt whatever plan is put in front of them. They fail because they have no coherent strategy.

At Cardiff Park we are advocates of sticking to a financial strategy that can be explained, observed, and verified. Our clients have good reasons to trust us, trust our strategy, trust the fund managers with whom we do business, and trust their results, even when disappointing. We’ll explain why.

The Rewards of Sticking to Strategy

At Cardiff Park, our investment strategy centers on passively managed index investing, including systematic investing as practiced by Dimensional and traditional indexing as practiced by Vanguard. Both organizations have cultures rooted in core values of integrity, focus, and stewardship, with a mission to do the right thing for clients. Vanguard’s unique client-owned structure enables them to return profits to fund shareholders in the form of lower expenses. Dimensional is privately owned and has a long history of applying academic research to practical investing. Since neither firm is beholden to public shareholders, cash flow isn't a short-term goal—it's an outcome of doing the right thing for clients over the long-term. Cardiff Park itself is an independent fiduciary, privately owned and responsible first and foremost to clients.

Dimensional creates structured portfolios that aim to minimize the weaknesses of classic indexing. These weaknesses include regular reconstitution to track the index, which can force selling low or buying high; forced trading that eliminates the potential to capture upward momentum; inclusion of all stocks in an index, which can expose the portfolio to poor risk-adjusted returns; and the ability to pursue tax-advantaged buying and selling opportunities.

Structured funds such as those offered by Dimensional accept greater tracking error risk in exchange for greater exposure to factors that have been historically proven to produce higher return premiums. These factors include size, value, momentum and profitability. For example, one US allocation fund might be structured to own smaller and more value-tilted stocks than another. Another fund might be structured to provide greater exposure to more profitable companies or the momentum effect.

Sizing Up the Numbers

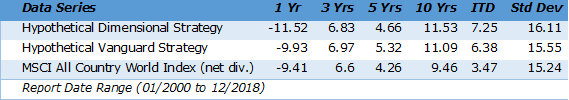

The following table compares returns for a hypothetical portfolio of equity index tracking funds from Vanguard to the returns of a systematically structured portfolio of asset class funds from Dimensional. We can’t directly compare apples to apples because Vanguard doesn’t have a matching component for every category. But we came close. Each portfolio is diversified across size and value asset classes within each category, targeting 60% US stocks, 23% International stocks, 10% Emerging Market stocks and 7% Real Estate securities. The weighted average expense ratio for the Vanguard construction is 12 basis points, whereas the weighted average expense ratio for the Dimensional construction is 33 basis points. The table provides the one, three, five, ten-year and inception-to-date returns for each strategy. See appendix for portfolio constructions. 1 2

Here is what we observe. As expected, both the Dimensional and Vanguard strategies outperformed the MSCI All Country World Index. This is due to their exposure to size and value asset classes as compared to a non-size-and-value tilted MSCI World Index. Even though Dimensional’s expense ratio is higher, the strategy’s more concentrated and consistent exposure to size and value premiums resulted in outperformance at 18 years, albeit with slightly higher standard deviation (risk).

If Dimensional wins the crown for outperformance over the full period, one might assume its allocation would outperform Vanguard for shorter periods of time as well. This wasn’t the case. As the table shows, Vanguard outperformed Dimensional over the 1, 3 and 5-year periods.

There are a few important takeaways. Both strategies did their jobs well. The differences in performance aren’t explained by good or bad management. Instead, they’re explained by each strategy’s structure and design—a passive index tracking strategy on one hand, and a systematically structured passive strategy on the other.

When the premiums are positive, you should expect the strategy with the most exposure to the size and value premiums to have the best results. And when the size and value premiums are negative, you should expect the one with the most exposure to these factors to underperform.

The following three charts show annual returns for the US components of the hypothetical strategies for the trailing 18 years. The selected period is based on the earliest common date of the underlying components. (See appendix for US category weights.3) The first chart shows that in 4 of the last 5 years, the Vanguard US allocation outperformed the Dimensional US allocation. The next two charts show the annual returns for the size and value premiums for the same span of time. What these charts demonstrate is that the negative performance of the size and value premiums in 4 of the last 5 years corresponds to the underperformance of the Dimensional US fund allocation. As expected, the strategy with most exposure to the size and value premiums underperformed when these factors did poorly.

This brings up an important concept that every investor should be aware of: recency bias. Recency bias is the psychological tendency of investors to allow recent returns to dominate decision-making while ignoring long-term evidence. One of the greatest problems preventing investors from achieving their financial goals is that when it comes to judging the performance of an investment strategy, they believe that three years is a long time, five years is a very long time and 10 years is an eternity. According to a 2018 report from DALBAR, which analyzes investor behavior, “the average mutual fund investor has not stayed invested for a long enough period of time to execute a long-term strategy. In fact, they stay invested for just a fraction of a market cycle.” The report goes on to say that over the last 20 years, “equity fund investors have seldom managed to stay invested for more than 4 years.” This has cost investors dearly. Even supposedly more sophisticated institutional investors—those who employ highly paid consultants—typically hire and fire managers based on the previous three years’ performance. On the other hand, financial economists know that when it comes to investment returns, 10 years can be nothing more than “noise,” a random outcome.

To provide some perspective on the benefits of fully committing for the long-term, let’s start with the long-term performance of US premiums. Here we see positive numbers for all the factors. Research shows the same conclusions can be drawn for Developed ex-US Markets and Emerging Markets.

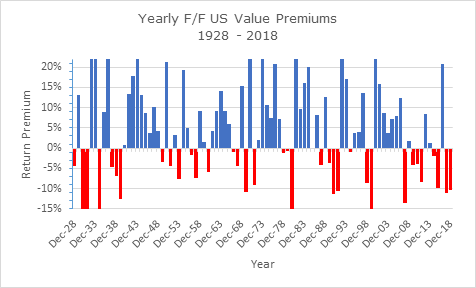

We expect the premiums to be positive on any given day, but we also know that on any given day or any given year the premiums may be positive or negative. To illustrate this point let’s take the US value premium. Since 1928, the long-term average for the value premium has been close to 5%. But if you look at how many years fall within 2% of that average, there are only a handful of observations. So, when we see a positive or negative premium of 10% or 20%, we shouldn’t be surprised, because we see this multiple times in the historical data.

It’s also interesting to note that there doesn’t seem to be any predictable pattern in the observations. It would be great if we could predict when the premium would be positive and just invest in stocks with concentrated exposure to the factor during that period, but research shows this is challenging to do.

If we move from yearly observations to 5-year observations, we see that the number of positive periods relative to the number of negative periods increases significantly.

And if we move from 5-year observations to 10-year observations we see the number of positive periods relative to the number of negative periods increase again.

This change is not just seen in the value premiums but is actually consistent across all the factors. As we look over longer time frames, we see more periods of positive outcomes.

So while we may experience a positive or negative premium in any given year, the data shows that as the time period increases, the probability of experiencing a positive premium increases as well.

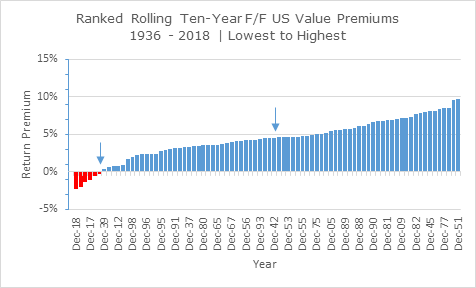

Many times, investors are interested in the magnitude of the return relative to historical observations. The chart below shows the performance of the value premium for 10-year periods, from lowest to highest. If you look at the recent 10-year period ending in 2018, you’ll see one of the most negative value premiums on record. But we need to be careful not to place too much emphasis on that single observation, because we know that a positive premium can show up quickly and in large magnitude. For example, if we look at one of the lowest 10-year periods visible in the data set below (1930-1939) we see a negative annualized value premium over that period. Moving forward just 3 years (1933-1942) we see a negative premium turn into a positive premium.

On the bottom line, returns of the hypothetical strategies we examined are well-explained by their exposure to common factors (market beta, size, value and quality). And while the Vanguard strategy has the lower expense ratio, it’s cost-per-unit of exposure that matters, not just overall cost. When designing your portfolio, you’ll want to take both factors into consideration. It might be that a particular fund with a higher expense ratio is the better choice, as it might have more exposure to the factors that determine returns and carry premiums. In other words, as the table of comparative results shows, it is not just cost that matters.

Commitment Counts

It takes courage to stick with strategy when you feel that the consequences of getting it wrong could have huge financial implications. But remember that your strategy is constructed on a solid framework of long-term research, analysis and regular review. Your asset allocation reflects your goals, objectives, risk tolerance and where you want to be in a defined period of time. You can’t eliminate risk. All investing carries risk, and every asset class, even cash, has its own risks. But one of the biggest risks, the one to seriously focus on, is failure to be fully committed to your strategy for the long-term.

You’re not in this alone. Your advisor (that’s us) and fund partners (Vanguard and DFA) can do all the right things, providing guidance and strategy while keeping costs low. But it’s also up to you to do the right things. That means committing to your strategy, staying on course, and making changes only when warranted. When it feels like things are going sideways, take a step back and keep things in perspective.

Do you have questions or concerns? Call me. I am here to help.

Regards

John Gorlow

President

Cardiff Park Advisors

888.332.2238 Toll Free

760.635.7526 Direct

760.271.6311 Cell

760.284.5550 Fax

jgorlow@cardiffpark.com

[1] Hypothetical Vanguard Portfolio: VFIAX (20%), VVIAX (20%), VSMAX (10%), VSAIX (10%), VINEX (8%), VTMGX (7.5%), VTRIX (7.5%), VEMAX (10%), VGSLX (7%). Hypothetical Dimensional Portfolio: DFUSX (20%), DFLVX (20%), DFSTX (10%), DFSVX (10%), DFISX (8%), DFALX (7.5%), DFIVX (7.5%), DEMSX (4%), DFEMX (3%), DFEVX (3%), DFREX (7%)

[2] Morningstar methodology substitutes investor share performance for admiral shares prior to admiral share inception dates, funds substituted include: VFIAX, VVIAX, VSMAX, VSIAX. The performance information for the Allocations are based on performance of funds with model/back-tested asset allocations and assumes all strategies have been rebalanced monthly. The allocations’ performance reflects the reinvestment of dividends and other earnings, and is net of fees. The performance was achieved with the benefit of hindsight; it does not represent actual investment strategies. There are limitations inherent in model allocations. In particular, model performance may not reflect the impact that economic and market factors may have had on the advisor’s decision making if the advisor were actually managing client money. The indices are not available for direct investment; therefore their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio. Past performance is no guarantee of future results, and there is always the risk that an investor may lose money.

[3] Hypothetical Vanguard US structure: VFIAX (33%), VVIAX (33%), VSMAX (17%), VSIAX (17%). Hypothetical Dimensional US structure: DFUSX (33%), DFLVX (33%), DFSTX (17%), DFSVX (17%)