John Gorlow

| Apr 14, 2020

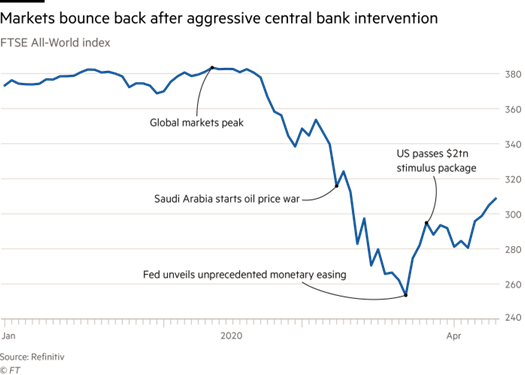

Just weeks after climbing to record heights, US stocks sank more than 30%, ending the longest bull market ever and returning stock prices to where they stood when President Trump took office in January 2017. Oil stocks slid to an 18-year low. A stampede out of bond markets and into cash added to the chaos. Many financial analysts believe that the value of private equity investments have been eroded even more than the broader stock market, due to the high leverage involved in most private equity deals.

Together, the speed of the decline in private equity and stock valuations unleashed a precipitous slide in bonds, currencies and commodities. The meltdown reflects the pace with which Covid-19 has spread fear around the world as nations, states and cities have been shuttered. As schools, workplaces, entertainment and non-essential retail enterprises closed, and strict restrictions on social gatherings stalled commerce, investors were confronted with a picture few could have imagined. It felt like all the wheels came off at once.

There was no time for investors to catch their breath, as panic-fueled trading began overnight when futures trading opened in Asian markets. For days and weeks, huge price swings were underway well before U.S. investors wiped the sleep from their eyes.

Markets have never unraveled as quickly as they did in the last month. Over the past few weeks, S&P 500 futures often dropped 5%, the maximum decline allowed under exchange rules. The S&P 500 dropped 7% on four occasions shortly after trading began, triggering circuit breakers designed to halt trading for 15 minutes during steep declines. The circuit breakers hadn’t been triggered since 1997. But beginning on 9-March, even the circuit breakers were helpless against the onslaught. That day, the S&P closed 7.6% lower. On Thursday, 12-March, the S&P 500 fell 9.5% and on Monday, 16-March, it slid 12% in its steepest one day drop since Black Monday in 1987.

Meanwhile, the yield on the benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury Note rose sharply after closing at 0.54% on 9-March. Yields rise as bond prices fall, and the declines in Treasuries, spurred by market disruptions and the unwinding of Wall Street bets, made the volatility even more painful. At the same time, investors shied away from corporate bonds, risky bank loans, municipal bonds and emerging market debt, driving record outflows in bond mutual funds. A deluge of credit downgrades at the fastest pace since 2002 put ratings agencies back in the spotlight, and further heightened investor anxiety.

Gold, another traditional haven, also peaked on 9-March, a sell-off prompted by investors forced to sell liquid assets to cover losses suffered in stocks. Some of that selling came after margin calls for those who had used stock as collateral to buy other securities. With the value of those positions shrinking, banks demanded repayment, triggering sales of unrelated assets. By the end of March gold had rebounded somewhat, but still closed down 6% for the period.

Commodity prices began falling as the virus took a big hit on economic activity in China in January, with price declines accelerating after Saudi Arabia and Russia launched an oil price war. The prospect of rising supply and crumbling demand sent U.S. crude oil down 50% for the month to about $22.50 a barrel, forcing a moment of truth for even the most vocal advocates of cheap oil.

Many analysts worried that the oil-price crash would result in bankruptcies of energy companies, some of which borrowed heavily in recent years. Investors were further spooked by fears that the fallout could damage lenders already struggling with the economic slowdown and the Federal Reserve’s 16-March decision to slash interest rates close to zero.

Strains in short-term money markets and critical markets like Treasuries caused the Federal Reserve to take additional steps to keep markets functioning properly, including buying $500 billion in Treasuries and $200 billion in mortgage-backed securities over the coming months. These measures extended to the currency markets, with concerns about a dollar shortage outside the U.S. driving the dollar Index (which tracks the dollar against 16 other currencies) to a nearly 18-year high.

Investors didn’t know which way to turn as they weighed a steep rise in Coronavirus cases, the shuttering of businesses and social interaction, and rising unemployment claims. The news kept getting worse. Delays in Washington on an economic rescue package added to the uncertainty. Markets extended their drop until bottoming out on Monday, 23-March.

Markets Soar on Hopes for Stimulus Deal

Then, on Tuesday, 24-March, the Dow notched its best day since 1933 as Congress and the White House neared a deal to inject nearly $2 trillion in aid into the economy to offer a lifeline to American families and industries on the brink of collapse. The Dow leaped 11.4% and the S&P 500 index jumped 9.4%. A wave of buying around the world interrupted what had been a brutal month of nearly non-stop declines. On Wednesday, 25-March, stocks rose again for their first back-to-back gains since February. By 31-March, the Dow and the S&P 500 Index rallied more than 15% since bottoming a week earlier, but remained down 20% from their February record levels. But even as stocks rebounded, March was the worst month for the bellwether indexes since October 2008, when investors feared a collapse of the economy in the global financial crisis. The S&P 500 dropped -12.5% for the month, and was down -20% for the year ending 31-March.

Fear, Uncertainty, and the Data Vacuum

From the vantage point of mid-April, we’re now looking over a battlefield of staggering casualties, with no good way to fully assess the damage. No one seems ready to assert that the worst of the market sell-off is over, or declare that the worst of the pandemic is over. Viewpoints range from optimism to pessimism. Seasoned, rational investors are trying to make up their minds about what to do. We’ll offer guidance in a moment but let’s first look at the situation.

Despite social distancing measures, 100,000 people worldwide have lost their lives to Covid-19, including more than 20,000 Americans. Two million cases have been confirmed globally. Estimated death rates in the U.S. range from 100,000 to 200,000 (U.S. health experts), to as many as one to two million people (British epidemiologist and disease forecaster Neil Ferguson).

Seventeen million Americans have applied for unemployment benefits. Consumer spending, the engine of the American economy, has ground to a halt. Some economists predict that the unemployment rate will approach 20% this spring, which would be about double the record in World War II and close to the 25% reached during the Great Depression. According to a study by Moody’s, at least one-quarter of the U.S. economy has been idled, with 8 of every 10 U.S. counties under lockdown orders. Wall Street economists are projecting unthinkable declines in gross domestic product (GDP) in the second quarter. Goldman Sachs expects the economy to shrink at a 24% annual rate, while Morgan Stanley economists expect it will be 30% or more.

All of this leads to the question of the moment: How long can we afford to keep the economy shut down? It’s a life or death question. Easing social distancing restrictions too soon could lead to a soaring death rate, while easing restrictions too late could lead to a spiraling downward economic cycle. Everyone agrees we need better data and reliable forecasts.

Essentially, economists agree we can’t achieve a fully functioning economy again until people are confident that they can go about their business without a high risk of catching Covid-19. That means figuring out how to re-open the economy while the virus still remains a risk—but a risk worth taking. Public health experts are making predictions about when the virus will peak, while many state governors are pleading for safe social distancing well after a peak occurs. When will the cost of ongoing business closures outweigh life-saving efforts to further slow the virus once the infection curve has flattened?

Data scientists, economists, health officials and policy makers are working around the clock to answer that question, but vital data is missing. The U.S. lacks the widespread testing capability needed to provide policy makers with information to make evidence-based decisions. Without more testing and monitoring, it’s impossible to determine when and how to open up workplaces. Better data would also help policy makers determine impacts on hospital and regional healthcare systems if infection rates flare up and spread after restrictions are lifted. Some economists believe aggressive suppression measures could lead to a gradual resumption of activity that begins in some regions as soon as four to six weeks. But business as usual might not fully return until a vaccine is developed or we get effective drug treatments, which could take more than a year.

Meanwhile, as we wait for infection rates to fall, policy makers must find ways to provide additional support to workers who have lost jobs and businesses teetering on the edge of collapse. There appears to be little national agreement on how to do this. “Let’s get back to work” sounds like a great idea, but a second spike in infections could do more damage to the economy than the first.

The New Normal

One doesn’t have to look very far down the road to understand how a post-Covid 19 world will be shaken and challenged. Industries will be in a weakened state. Households mired in debt may be risk-averse, causing a slow return to consumer spending. Some societal distancing measures could remain indefinitely, causing ongoing pain to businesses large and small. Despite the best efforts of central banks and governments to soften the economic blows, the likelihood of avoiding a global recession is uncertain.

In developing countries, the consequences of miscalculations will be harsher. Many low-income countries are only now being hit by the pandemic. Cases in Africa have climbed to more than 10,000, with 750 confirmed deaths. If the Coronavirus winds through packed cities, refugee camps and war zones, the human toll could prove to be devastating. And yet, just as urgent action is needed to help protect the world’s poorest countries, capital is fleeing. A plunge in commodity prices, especially oil, is adding to the pain in many countries, including Mexico, Chile and Nigeria. China’s slowdown is rippling out to places including Indonesia and South Korea, which supplied Chinese factories with components.

This bad news comes on top of staggering debt. Between now and the end of next year, developing countries are on the hook to repay some $2.7 trillion in debt. In normal times they could afford to roll most of that borrowing into new loans. But the abrupt exodus of money has prompted higher borrowing costs. The United Nations has called for a $2.5 trillion rescue fund for developing countries.

From a more optimistic point of view, the beginnings of an economic fix are underway. China has reportedly contained the virus and is gradually getting back to work. When Chinese factories spring back to life there may be a ripple effect across the globe, generating demand for computer chips made in Taiwan, copper mined in Zambia and soy-beans grown in Argentina.

Then and Now

As the groundwork is being laid to gradually reopen the economy, investors face a choice. Is it wise to piggyback on the government and central bank support pouring into financial markets and snap up assets while prices are still beaten up? This could be the buying opportunity of a lifetime. Or will this shakeout continue to drive markets down? No one knows. Regardless of which way the tide turns, extreme caution may no longer be warranted, given the steep drop in asset prices and the wave of central bank support that has neutralized some risks. It’s a good time to remember what we know about markets: They always come back from major disruptions, though it may take longer than we like. Consider the following market synopsis from the WSJ (Sarah Williamson and Mark Wiseman, 17-March 2020).

The 2007-2008 global financial crisis is a good example. The U.S. economy contracted 2.5% in 2009 but by 2010 the economy was growing again at pre-meltdown rates. By 2013, stocks had largely recovered.

The 9/11 attacks also shocked markets in the short-term but left them with no significant damage over the long-term. It took only one month for stocks to regain their pre 9/11 price levels.

A third case in point is the 1973 oil crisis. After the oil embargo, GDP growth fell from 5.6% in 1973 to minus 0.5% in 1974 and minus 0.2% in 1975. In 1976, GDP came roaring back to with 5.4% annual growth. GDP growth recovered within 3 years of the initial event, as it did following 9/11 and the 2007-2008 financial crisis. Here’s another case that may feel closest to our current situation.

The Spanish flu of 1918-19 is widely regarded as the most devastating pandemic of modern times, caused a massive supply shock as millions were unable to work. Demand cratered as people stayed home and events around the world were canceled for fears of spreading the contagion. The Dow lost 40% of its value between January 1919 and continued to decline until December 1920. But within three years of the initial crisis markets began to recover, then rose for nearly a decade.

Collectively, these events, spanning more than a century, show that markets almost always recover in the long run. Investors shouldn’t ignore short-term circumstances, but neither should they abandon well crafted plans for the future.

Another Scenario

But wait a minute. What if everything gets worse, and the projections of Dr. Neil Ferguson are correct? How would markets respond if his worst-case scenario of two million U.S. deaths came to pass? The crisis would then be a wake-up call to address long-term vulnerabilities. That might mean providing universal health coverage, paid sick leave and some form of guaranteed income. More broadly, the U.S. would have no choice but to shift priorities and fund massive public health initiatives. What if this is the first of multiple pandemics? What if scientists are unable to develop effective treatments? What if the outbreak puts stress on the food chain, disrupts distribution of other goods, or leads to social unrest?

A Conservative Approach

The market may be underestimating the mid-term risk to the economy from a delayed US peak and the volatility that could result for global stock markets. Again, no way to know. But you do know how much discomfort you can live with. Imagine a stock market decline of more than 50%, in line with the frightening bear market of October 2007 through February 2009. Figure out how much liquidity you’ll want to have on hand and how much you’ll want to have invested by the time the bottom is reached, and then undertake gradual rebalancing to reach that objective. Stocks may continue to head north, and you’ll be glad you bought some. Or they may head south, in which case you’ll have money left to buy more and also to avoid putting yourself in a position in which you must make urgent short-term sales. It’s very likely that more aggressive strategies will pay off for investors who can afford to wait, but that could take some time.

On the other hand, even though this isn’t an ideal time to sell stock, because prices have already dropped considerably, they may well fall further. If you already know, from recent experience, that you couldn’t handle that, by all means sell and switch to investments that you can live with, recommends David Booth of DFA. His words of wisdom: The text book answer is to find an asset allocation you can live with for a long time. But people in distress don’t care about textbooks, this isn’t science. It’s about human behavior. And if you are freaking out, the first thing is to find a way to get comfortable. Perhaps that means getting out of stocks, better yet, is to find a way to live with stocks. That may mean that you need a more conservative approach than you felt comfortable with just a few months ago.

In Sum: We Don’t Know

The Coronavirus has exacted great human and financial costs. Right now, investors are reassessing expectations for the future. More to the point, everyone from the largest tech companies to national governments to global airlines are assessing the potential impact on the global economy. Markets process information in real-time as it becomes available, but the market is pricing in unknowns, too. We see this happening when markets decline sharply as well as when they rise swiftly. As risk increases during times of heightened uncertainty, so do the returns investors demand for bearing that risk, which push stock prices lower.

Since there’s no reliable way to identify a market peak or bottom, the best strategy is to find an asset allocation you can live with rather than making moves based on fear or speculation, even in the face of traumatic events. At times it can be hard to stay the course. There are always alternatives. Please reach out if you would like our help to adjust your holdings. Meanwhile, stay safe and healthy.

Regards,

John Gorlow

President

Cardiff Park Advisors

888.332.2238 Toll Free>

760.635.7526 Direct

760.271.6311 Cell

760.284.5550 Fax

jgorlow@cardiffpark.com

Q1 2020 Market Report

Courtesy of DFA

World Asset Classes

Equity markets around the globe posted negative returns in the first quarter. Looking at broad market indices, US equities outperformed non-US developed markets and emerging markets. Value stocks underperformed growth stocks in all regions. Small caps also underperformed large caps in all regions. REIT indices underperformed equity market indices in both the US and non-US developed markets.

|

World Asset Classes

|

QTD

|

|

Bloomberg Barclays US Aggregate Bond Index

|

3.15

|

|

One-Month US Treasury Bills

|

0.37

|

|

S&P 500 Index

|

-19.6

|

|

Russell 1000 Index

|

-20.22

|

|

Russell 3000 Index

|

-20.9

|

|

MSCI World ex USA Index (net div.)

|

-23.26

|

|

MSCI All Country World ex USA Index (net div.)

|

-23.36

|

|

MSCI Emerging Markets Index (net div.)

|

-23.6

|

|

Russell 1000 Value Index

|

-26.73

|

|

MSCI Emerging Markets Value Index (net div.)

|

-28

|

|

MSCI World ex USA Small Cap Index (net div.)

|

-28.39

|

|

Dow Jones US Select REIT Index

|

-28.52

|

|

MSCI World ex USA Value Index (net div.)

|

-28.76

|

|

Russell 2000 Index

|

-30.61

|

|

MSCI Emerging Markets Small Cap Index (net div.)

|

-31.37

|

|

S&P Global ex US REIT Index (net div.)

|

-32.5

|

|

Russell 2000 Value Index

|

-35.66

|

|

First Quarter 2020 Index Returns

|

|

US Stocks

The US equity market posted negative returns for the quarter but on a broad index level outperformed non-US developed markets and emerging markets. Value underperformed growth in the US across large and small cap stocks. Small caps underperformed large caps in the US. REIT indices underperformed equity market indices.

|

Ranked Returns for the Quarter

|

%

|

|

Russell 1000 Growth Index

|

-14.10

|

|

Russell 1000 Index

|

-20.22

|

|

Russell 3000 Index

|

-20.90

|

|

Russell 2000 Growth Index

|

-25.76

|

|

Russell 1000 Value Index

|

-26.73

|

|

Russell 2000 Index

|

-30.61

|

|

Russell 2000 Value Index

|

-35.66

|

|

First Quarter 2020 Index Returns

|

|

|

Period Returns (%)

|

QTD

|

1 Yr

|

3 Yrs*

|

5 Yrs*

|

10 Yrs*

|

|

Russell 1000 Growth Index

|

-14.10

|

0.91

|

11.32

|

10.36

|

12.97

|

|

Russell 1000 Index

|

-20.22

|

-8.03

|

4.64

|

6.22

|

10.39

|

|

Russell 3000 Index

|

-20.90

|

-9.13

|

4.00

|

5.77

|

10.15

|

|

Russell 2000 Growth Index

|

-25.76

|

-18.58

|

0.10

|

1.70

|

8.89

|

|

Russell 1000 Value Index

|

-26.73

|

-17.17

|

-2.18

|

1.90

|

7.67

|

|

Russell 2000 Index

|

-30.61

|

-23.99

|

-4.64

|

-0.25

|

6.90

|

|

Russell 2000 Value Index

|

-35.66

|

-29.64

|

-9.51

|

-2.42

|

4.79

|

|

As of 03/31/2020

|

|

|

* Annualized

|

International Developed Stocks

Developed markets outside the US underperformed the US equity market but outperformed emerging markets equities during the quarter. Small caps underperformed large caps in non-US developed markets. Value underperformed growth across large and small cap stocks.

|

Ranked Returns for the Quarter

|

%

|

|

MSCI World ex USA Growth Index (net div.)

|

-15.06

|

|

MSCI World ex USA Index (net div.)

|

-20.52

|

|

MSCI World ex USA Small Cap Index (net div.)

|

-25.45

|

|

MSCI World ex USA Value Index (net div.)

|

-26.05

|

|

First Quarter 2020 Index Returns

|

|

|

Period Returns (%)

|

QTD

|

1 Yr

|

3 Yrs*

|

5 Yrs*

|

10 Yrs*

|

|

MSCI World ex USA Growth Index (net div.)

|

-17.81

|

-6.47

|

2.55

|

2.05

|

4.25

|

|

MSCI World ex USA Index (net div.)

|

-23.26

|

-14.89

|

-2.07

|

-0.76

|

2.43

|

|

MSCI World ex USA Small Cap Index (net div.)

|

-28.39

|

-19.04

|

-3.60

|

0.39

|

3.95

|

|

MSCI World ex USA Value Index (net div.)

|

-28.76

|

-23.16

|

-6.74

|

-3.70

|

0.51

|

|

As of 03/31/2020

|

|

* Annualized

|

Emerging Markets Stocks

Emerging markets underperformed developed markets, including the US, for the quarter. Value stocks underperformed growth stocks. Small caps underperformed large caps.

|

Ranked Returns for the Quarter

|

%

|

|

MSCI Emerging Markets Growth Index (net div.)

|

-14.69

|

|

MSCI Emerging Markets Index (net div.)

|

-19.05

|

|

MSCI Emerging Markets Value Index (net div.)

|

-23.57

|

|

MSCI Emerging Markets Small Cap Index (net div.)

|

-26.37

|

|

First Quarter 2020 Index Returns

|

|

|

Period Returns (%)

|

QTD

|

1 Yr

|

3 Yrs*

|

5 Yrs*

|

10 Yrs*

|

|

MSCI Emerging Markets Growth Index (net div.)

|

-19.34

|

-9.94

|

2.39

|

2.13

|

2.71

|

|

MSCI Emerging Markets Index (net div.)

|

-23.60

|

-17.69

|

-1.62

|

-0.37

|

0.68

|

|

MSCI Emerging Markets Value Index (net div.)

|

-28.00

|

-25.26

|

-5.78

|

-3.00

|

-1.45

|

|

MSCI Emerging Markets Small Cap Index (net div.)

|

-31.37

|

-28.98

|

-9.64

|

-5.17

|

-1.34

|

|

As of 03/31/2020

|

|

* Annualized

|

Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs)

US real estate investment trusts outperformed non-US REITs in US dollar terms during the quarter.

|

Ranked Returns for the Quarter

|

%

|

|

Dow Jones US Select REIT Index

|

-28.52

|

|

S&P Global ex US REIT Index (net div.)

|

-32.50

|

|

First Quarter 2020 Index Returns

|

|

|

Period Returns (%)

|

QTD

|

1 Yr

|

3 Yrs*

|

5 Yrs*

|

10 Yrs*

|

|

Dow Jones US Select REIT Index

|

-28.52

|

-23.96

|

-4.28

|

-1.42

|

6.88

|

|

S&P Global ex US REIT Index (net div.)

|

-32.50

|

-25.34

|

-4.83

|

-2.76

|

3.61

|

|

As of 03/31/2020

|

|

* Annualized

|

Commodities

The Bloomberg Commodity Index Total Return decreased 23.29% for the first quarter.

|

Period Returns (%)

|

QTD

|

1 Yr

|

3 Yrs*

|

5 Yrs*

|

10 Yrs*

|

|

Commodities

|

-23.29

|

-22.31

|

-8.61

|

-7.76

|

-6.74

|

|

As of 03/31/2020

|

|

* Annualized

|

Fixed Income

Interest rates decreased in the US treasury market in the first quarter. The yield on the 5-year Treasury note decreased by 132 basis points (bps), ending at 0.37%. The yield on the 10-year note decreased by 122 bps to 0.70%. The 30-year Treasury bond yield decreased 104 bps to 1.35%.

On the short end of the yield curve, the 1-month Treasury bill yield decreased to 0.05%, while the 1-year Treasury bill yield decreased by 142 bps to 0.17%. The 2-year note finished at 0.23% after a decrease of 135 bps.

In terms of total returns, short-term corporate bonds declined 2.19%. Intermediate-term corporate bonds declined 3.15%.The total return for short-term municipal bonds was -0.51%, while intermediate muni bonds returned -0.82%. General obligation bonds outperformed revenue bonds.

|

Bond Yields Across Issuers

|

(%)

|

|

10-Year US Treasury

|

0.70

|

|

State and Local Municipals

|

2.87

|

|

AAA-AA Corporates

|

2.38

|

|

A-BBB Corporates

|

3.84

|

|

First Quarter 2020 Index Returns

|

|

|

Period Returns (%)

|

QTR

|

1 Yr

|

3 Yrs*

|

5 Yrs*

|

10 Yrs*

|

|

Bloomberg Barclays US Gov't Bond Index Long

|

20.63

|

32.28

|

13.30

|

7.32

|

8.89

|

|

Bloomberg Barclays US Aggregate Bond Index

|

3.15

|

8.93

|

4.82

|

3.36

|

3.88

|

|

FTSE World Gov't Bond Indx 1-5 Years USD Hedged

|

2.25

|

4.98

|

3.03

|

2.24

|

2.00

|

|

ICE BofA 1-Year US Treasury Note Index

|

1.72

|

3.85

|

2.31

|

1.57

|

0.98

|

|

Bloomberg Barclays US TIPS Index

|

1.69

|

6.85

|

3.46

|

2.67

|

3.48

|

|

FTSE World Government Bond Index 1-5 Years

|

0.69

|

2.79

|

2.12

|

1.55

|

0.40

|

|

ICE BofA US 3-Month Treasury Bill Index

|

0.57

|

2.25

|

1.83

|

1.19

|

0.64

|

|

Bloomberg Barclays Municipal Bond Index

|

-0.63

|

3.85

|

3.96

|

3.19

|

4.15

|

|

Bloomberg Barclays US High Yield Corp Bond Index

|

-12.68

|

-6.94

|

0.77

|

2.78

|

5.64

|

|

As of 03/31/2020

|

|

|

* Annualized

|

Global Fixed Income

Government bond interest rates in the global developed markets generally decreased during the quarter. Longer-term bonds generally outperformed shorter-term bonds in the global developed markets. Short- and intermediate-term nominal interest rates are negative in Japan and Germany.

|

Changes in Yields (bps) since 12/31/2019

|

|

|

1Y

|

5Y

|

10Y

|

20Y

|

30Y

|

|

US

|

-1.51

|

-1.28

|

-1.24

|

-1.10

|

-0.98

|

|

UK

|

-0.48

|

-0.41

|

-0.46

|

-0.47

|

-0.49

|

|

Germany

|

0.10

|

-0.20

|

-0.28

|

-0.29

|

-0.31

|

|

Japan

|

-0.02

|

0.01

|

0.07

|

0.05

|

0.02

|

|

Canada

|

-1.31

|

-1.10

|

-0.93

|

-0.48

|

-0.42

|

|

Australia

|

-0.71

|

-0.70

|

-0.61

|

-0.31

|

-0.34

|

|

As of 03/31/2020

|

Impact of Diversification

These portfolios illustrate the performance of different global stock/bond mixes and highlight the benefits of diversification. Mixes with larger allocations to stocks are considered riskier but have higher expected returns over time.

|

Ranked Returns for the Quarter

|

%

|

|

100% Treasury Bills

|

0.37

|

|

25/75

|

-5.29

|

|

50/50

|

-10.78

|

|

75/25

|

-16.10

|

|

100% Stocks

|

-21.26

|

|

First Quarter 2020 Index Returns

|

|

|

Period Returns (%)

|

QTD

|

1 Yr

|

3 Yrs*

|

5 Yrs*

|

10 Yrs*

|

10-Yr STDEV

|

|

100% Treasury Bills

|

0.37

|

1.93

|

1.67

|

1.06

|

0.56

|

0.23

|

|

25/75

|

-5.29

|

-1.03

|

1.98

|

1.83

|

2.19

|

3.50

|

|

50/50

|

-10.78

|

-4.14

|

2.15

|

2.48

|

3.72

|

7.00

|

|

75/25

|

-16.1

|

-7.39

|

2.17

|

3.01

|

5.14

|

10.50

|

|

100% Stocks

|

-21.26

|

-10.76

|

2.05

|

3.41

|

6.45

|

14.00

|

|

As of 03/31/2020

|

|

* Annualized

|

Footnotes

1. STDEV (standard deviation) is a measure of the variation or dispersion of a set of data points. Standard deviations are often used to quantify the historical return volatility of a security or portfolio.

2. Diversification does not eliminate the risk of market loss. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Indices are not available for direct investment. Index performance does not reflect expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio. Asset allocations and the hypothetical index portfolio returns are for illustrative purposes only and do not represent actual performance. Global Stocks represented by MSCI All Country World Index (gross div.) and Treasury Bills represented by US One-Month Treasury Bills. Globally diversified allocations rebalanced monthly, no withdrawals. Data © MSCI 2020, all rights reserved. Treasury bills © Stocks, Bonds, Bills, and Inflation Yearbook™, Ibbotson Associates, Chicago (annually updated work by Roger G. Ibbotson and Rex A. Sinquefield). .

3. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Market segment (index representation) as follows: US Stocks—Large Cap (Russell 1000 Index), Small Cap (Russell 2000 Index), Growth (Russell 3000 Growth Index), Value (Russell 3000 Value Index); Developed ex US Stocks—Large Cap (MSCI World ex USA Index), Small Cap (MSCI World ex USA Small Cap Index), Value (MSCI World ex USA Value Index), Growth (MSCI World ex USA Growth Index); Emerging Markets Stocks—Large Cap (MSCI Emerging Markets Index), Small Cap (MSCI Emerging Markets Small Cap Index), Value (MSCI Emerging Markets Value Index), Growth (MSCI Emerging Markets Growth Index). Index returns are in US dollars, MSCI indices are net of withholding tax on dividends. Frank Russell Company is the source and owner of the trademarks, service marks, and copyrights related to the Russell Indexes. MSCI data © MSCI 2020, all rights reserved. Indices are not available for direct investment. Index performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio.

4. The information herein is provided in good faith without any warranty and is intended for the recipient’s background information only. It does not constitute investment advice, recommendation, or an offer of any services or products for sale and is not intended to provide a sufficient basis on which to make an investment decision. Cardiff Park Advisors accepts no responsibility for loss arising from the use of the information contained herein.